Written by Tom

[Previously: The DC Cinematic Universe vs. the World – The Story So Far]

Shazam! is the DCEU’s hidden gem. The sole entry in the mainline DCEU to have nothing to do with Harley Quinn or the Justice League, it seems to have become the film that’s most commonly forgotten when talking about the franchise overall. It also can’t have helped that the film sits pretty thoroughly in the shadow of Aquaman – director David F. Sandberg got the job because he had worked with Aquaman director James Wan on his Annabelle films, and it directly continues many of the techniques and tones which Aquaman brought to the table. This is very unfair on Shazam! though, ignoring the many things which are unique to it while underselling just how much the DCEU needed a “business as usual” film at the time.

You see, the story of the DCEU up until Aquaman is that of a franchise tearing itself apart. Each film either tries to encapsulate the DCEU house-style while visibly failing or is a direct attempt to reconfigure that house-style into something new. It’s not really until Aquaman that you get a film which feels like a DCEU movie while also feeling stable enough to be repeatable. As such, what the series really needed post-Aquaman was a film to successfully redo what Aquaman did while still turning a profit, proving that the DCEU finally had a workable set-up that future films could use. That’s what Shazam! did.

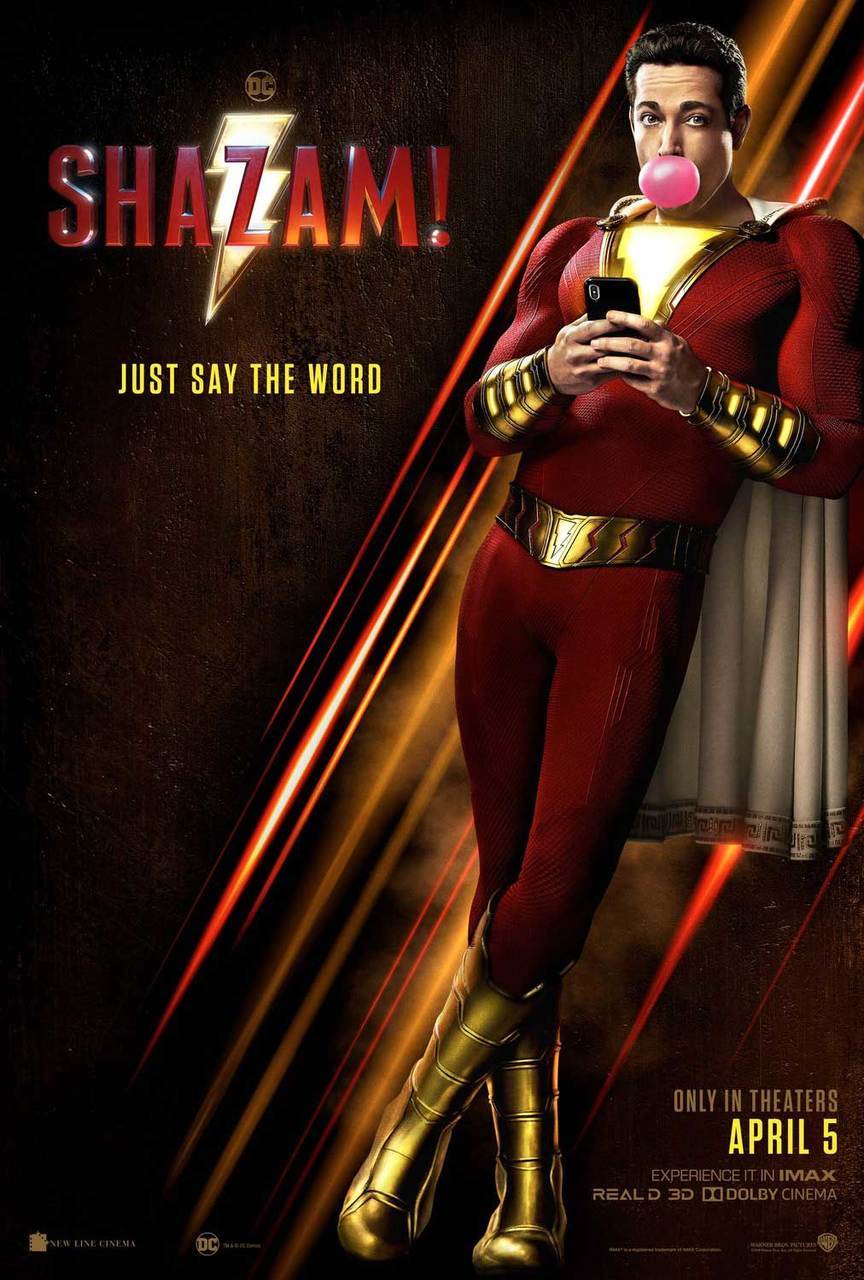

So what is this new aesthetic? Well let’s be honest, it’s basically the decision to be colourful and fun. Shazam! tells the story of teenager Billy Batson who becomes the superhero Shazam after being given powers by an ancient wizard. It pitches this story as a straightforward comedy, actively mining the disjunct between Billy Batson’s teenage immaturity and the hypermasculine iconography of Shazam for all its worth. This mining then feeds into Shazam!‘s thematic concerns. Upon gaining his powers, Billy’s first actions are to buy beer, go to a strip club and become YouTube famous. These are all adult activities but they’re the types of adult activities that a young boy would want to do first. So we get a film which is about combining childish spaces with adult ones, using the duality of its main character to skip from one to the other with glee.

This turns Shazam! into an excellent children’s movie. A lot of children’s literature is about child characters entering foreign locations and having to figure out how they work, using this as a metaphor for growing up and figuring out your place in the world. That’s what happens here: Billy Batson is transported by a wizard to an ancient cave and given powers so that he can fight in an secret war against the Seven Deadly Sins. He both becomes aware of ancient history and an active participant in it, removed from the blissfully ignorant time of childhood and forced to carve out a space within the world at large. In doing so, he also gets a visibly older body that has new abilities he must figure out. The metaphor for puberty isn’t hard to spot there.

Shazam! isn’t entirely about growing up though. Billy Batson’s childhood isn’t ideal or particularly sheltered – he’s an orphan who has spent his time getting into trouble and being thrown around foster homes. If childhood is meant to be unfettered and free, then his isn’t, defined by great periods of time in which he’s been stuck in various institutions, a cog in a much greater system, quite like a worker. As such, becoming Shazam is a liberatory moment for him – one in which he gets bestowed with power that lets him do whatever he wants. Becoming a superhero isn’t just a metaphor for growing up and accepting responsibility to him, it’s also a way of breaking away from the world and reclaiming the ability to be childish. In Shazam!, superheroism is a way of bridging the gap between childhood and adulthood – of neither becoming an adult nor a child but embracing both states at the same time.

This is a deft way of looking at superheroes. Superhero comics have been traditionally seen outside of comics fandom as children’s material. This presumably comes from their origins as pulp fiction, taking the form of cheaply printed booklets which were sold for cents during the Great Depression and which caught on with kids because they were image-heavy adventure stories which could be bought with pocket money. Children were just one audience for pulp fiction though – pulp fiction was popular because it was cheap enough to be bought by anyone, particularly when times were tough. As such, superheroes were not just childish ideals to be grown into but also represented the fantasies of resistance and self-sustenance, something which would’ve particularly resonated with a downtrodden population trying to scrape a living within an economic catastrophe. This resulted in one of the weird dichotomies of superheroes – they visibly represent the childish desire of being able to either fly away from your problems or beat them into submission, yet this is a desire built from adult concerns where neither of those things are usually an option. Superheroes are both adult and childish figures, providing a childish view of the adult world alongside the fantasy that the childish view can win in the end.

This is what Shazam! embodies and is a tribute to. It isn’t particularly interested in the concept of self-sustenance though. Struggling to face his first supervillain and having spent too little time training to fight, Billy comes up with an idea – if he was made into a superhero through magic, why can’t he use magic to make the other children in his foster home into superheroes too? So that’s what he does. The optics to this are fabulous. The other people in his foster home are disadvantaged children just like him, most of whom are either disabled or women/non-white. As such, it’s a nice touch that the best thing that Billy can do with his power is to share it. The reason why superheroes have become so powerful in our society is because, despite representing the ability of certain individuals to withstand anything thrown at them, the superhero genre is a collectivist phenomenon. They speak on people en-masse and provide a utopian fantasy which is shared amongst thousands. To have Shazam! reflect that, particularly given how focussed it is on a child audience – to in effect be telling a generation of children that the best thing to do with power is share it so that your society can work collectively to defeat its ills – well, that’s what the superhero genre is here for. This is the superhero movie as a social good.

Which gets us at the defining element of Aquaman and Shazam! – their utter joy at being superhero movies. Aquaman treats the genre as a toybox, using it as an excuse to produce every film scene James Wan has ever wanted to do. Shazam! limits itself to much lower stakes but, in doing so, remembers what’s actually important to superheroes – childishness and the ways it can be used as a prism to improve the adult world. The DCEU has gone from being suspicious of superhero movies to being their greatest champions. The James Wan era is defined by its joyous optimism.